K–Ar dating

Potassium–argon dating or K–Ar dating is a radiometric dating method used in geochronology and archeology. It is based on measurement of the product of the radioactive decay of an isotope of potassium (K) into argon (Ar). Potassium is a common element found in many materials, such as micas, clay minerals, tephra, and evaporites. In these materials, the decay product 40Ar is able to escape the liquid (molten) rock, but starts to accumulate when the rock solidifies (recrystallises). Time since recrystallization is calculated by measuring the ratio of the amount of 40Ar accumulated to the amount of 40K remaining. The long half-life of 40K allows the method to be used to calculate the absolute age of samples older than a few thousand years.[1]

The quickly cooled lavas that make nearly ideal samples for K–Ar dating also preserve a record of the direction and intensity of the local magnetic field as the sample cooled past the Curie temperature of iron. The geomagnetic polarity time scale was calibrated largely using K–Ar dating.[2]

Contents |

Decay series

Potassium naturally occurs in 3 isotopes – 39K (93.2581%), 40K (0.0117%), 41K (6.7302%). The radioactive isotope 40K decays with a half-life of 1.248×109 yr to 40Ca and 40Ar. Conversion to stable 40Ca occurs via electron emission (beta decay) in 89.1% of decay events. Conversion to stable 40Ar occurs via positron emission (inverse beta decay, electron capture) in the remaining 10.9% of decay events.[3]

Argon, being a noble gas, is a minor component of most rock samples of geochronological interest: it does not bind with other atoms in a crystal lattice. When 40K decays to 40Ar, the atom typically remains trapped within the lattice because it is larger than the spaces between the other atoms in a mineral crystal. But it can escape into the surrounding region when the right conditions are met, such as change in pressure and/or temperature. 40Ar atoms are able to diffuse through and escape from molten magma because most crystals have melted and the atoms are no longer trapped. Entrained argon—diffused argon that fails to escape from the magma—may again become trapped in crystals when magma cools to become solid rock again. After the recrystallization of magma, more 40K will decay and 40Ar will again accumulate, along with the entrained argon atoms, trapped in the mineral crystals. Measurement of the quantity of 40Ar atoms is used to compute the amount of time that has passed since a rock sample has solidified.

Calcium is common in the crust, with 40Ca being the most abundant isotope. Despite 40Ca being the favored daughter nuclide, its usefulness in dating is limited since a great many decay events are required for a small change in relative abundance, and also the amount of calcium originally present may not be known.

Formula

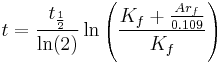

The ratio of the amount of 40Ar to that of 40K is directly related to the time elapsed since the rock was cool enough to trap the Ar by the following equation:

- t is time elapsed

- t1/2 is the half-life of 40K

- Kf is the amount of 40K remaining in the sample

- Arf is the amount of 40Ar found in the sample.

The scale factor 0.109 corrects for the unmeasured fraction of 40K which decayed into 40Ca; the sum of the measured 40K and the scaled amount of 40Ar gives the amount of 40K which was present at the beginning of the elapsed time period. In practice, each of these values may be expressed as a proportion of the total potassium present, as only relative, not absolute, quantities are required.

Obtaining the data

To obtain the content ratio of isotopes 40Ar to 39K in a rock or mineral, the amount of Ar is measured by mass spectrometry of the gases released when a rock sample is melted in flame photometry or atomic absorption spectroscopy.

The amount of 40K is rarely measured directly. Rather, the more common 39K is measured and that quantity is then multiplied by the accepted ratio of 40K/39K (i.e., 0.0117%/93.2581%, see above).

The amount of 36Ar may also be required to be measured.

Assumptions

According to McDougal and Harrison (1999, p. 11) the following assumptions must be true for computed dates to be accepted as representing the true age of the rock [4]

- The parent nuclide, 40

K, decays at a rate independent of its physical state and is not affected by differences in pressure or temperature. This is a well founded major assumption, common to all dating methods based on radioactive decay. Although changes in the electron capture partial decay constant for 40

K possibly may occur at high pressures, theoretical calculations indicate that for pressures experienced within a body of the size of the Earth the effects are negligibly small.[1]

- The 40

K/39

K ratio in nature is constant so the 40

K is rarely measured directly, but is assumed to be 0.0117% of the total potassium. Unless some other process is active at the time of cooling, this is a very good assumption for terrestrial samples.[5]

- The radiogenic argon measured in a sample was produced by in situ decay of 40

K in the interval since the rock crystallized or was recrystallized. Violations of this assumption are not uncommon. Well-known examples of incorporation of extraneous 40

Ar include chilled glassy deep-sea basalts that have not completely outgassed preexisting 40

Ar*,[6] and the physical contamination of a magma by inclusion of older xenolitic material. The Ar–Ar dating method was developed to measure the presence of extraneous argon.

- Great care is needed to avoid contamination of samples by absorption of nonradiogenic 40

Ar from the atmosphere. The equation may be corrected by subtracting from the 40

Armeasured value the amount present in the air where 40

Ar is 295.5 times more plentiful than 36

Ar. 40

Ardecayed = 40

Armeasured − 295.5 × 36

Armeasured.

- The sample must have remained a closed system since the event being dated. Thus, there should have been no loss or gain of 40

K or 40

Ar*, other than by radioactive decay of 40

K. Departures from this assumption are quite common, particularly in areas of complex geological history, but such departures can provide useful information that is of value in elucidating thermal histories. A deficiency of 40

Ar in a sample of a known age can indicate a full or partial melt in the thermal history of the area. Reliability in the dating of a geological feature is increased by sampling disparate areas which have been subjected to slightly different thermal histories.[7]

Both flame photometry and mass spectrometry are destructive tests, so particular care is needed to ensure that the aliquots used are truly representative of the sample. Ar–Ar dating is a similar technique which compares isotopic ratios from the same portion of the sample to avoid this problem.

Applications

Due to the long half-life, the technique is most applicable for dating minerals and rocks more than 100,000 years old. For shorter timescales, it is likely that not enough Argon 40 will have had time to accumulate in order to be accurately measurable. K–Ar dating was instrumental in the development of the geomagnetic polarity time scale.[2] Although it finds the most utility in geological applications, it plays an important role in archaeology. One archeological application has been in bracketing the age of archeological deposits at Olduvai Gorge by dating lava flows above and below the deposits.[8] It has also been indispensable in other early east African sites with a history of volcanic activity such as Hadar, Ethiopia.[8] The K–Ar method continues to have utility in dating clay mineral diagenesis.[9] Clay minerals are less than 2 micrometres thick and cannot easily be irradiated for Ar–Ar analysis because Ar recoils from the crystal lattice.

Notes

- ^ a b McDougal and Harrison 1999, p. 10

- ^ a b McDougal and Harrison 1999, p. 9

- ^ "ENSDF Decay Data in the MIRD Format for <sup40K". National Nuclear Data Center. http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/useroutput/40k_mird.html. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ^ McDougal and Harrison & 1999 "As with all isotopic dating methods, there are a number of assumptions that must be fulfilled for a K–Ar age to relate to events in the geological history of the region being studied., p. 11

- ^ McDougal and Harrison 1999, p. 14

- ^ 40

Ar* means radiogenic argon - ^ McDougal and Harrison 1999, pp. 9–12

- ^ a b Tattersall, 1995

- ^ Aronson and Lee, (1986)

References

- Ian McDougall and T. Mark Harrison (1999), Geochronology and thermochronology by the 40Ar/39Ar method, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-510920-1.

- Ian Tattersall (1995), The Fossil Trail: How We Know What We Think We Know About Human Evolution, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-506101-2.

Further reading

- "K/Ar and 40K/39K methodology". New Mexico Geochronology Research Laboratory. http://www.ees.nmt.edu/Geol/labs/Argon_Lab/Methods/Methods.html.

- George H. Michaels and Brian M. Fagan (15 December 2005). "Chronological Methods 9: Potassium–Argon Dating". University of California. http://id-archserve.ucsb.edu/Anth3/Courseware/Chronology/09_Potassium_Argon_Dating.html.

- James L. Aronson and Mingchou Lee (1986). "K/Ar systematics of bentonite and shale in a contact metamorphic zone". Clays and Clay Minerals 34: 483–487. doi:10.1346/CCMN.1986.0340415.

- "Teaching Radioisotope Dating Using the Geology of the Hawaiian Islands". Journal of Geoscience Education. http://mast.unco.edu/JGE-PDFs/MAR/p101-105MAR2009Moran.pdf.